Chen Shi Hunyuan Taijiquan 陳式混元太極拳

Our story starts back in the mid-1600s, the last decades of the once great Ming Dynasty of China. It was at this time, as the Ming government collapsed in 1644, that a general by the name of Chen Wangting (陳王庭; 1580-1660) retired from military service and returned home to the Chen family village in Henan Province.

In his retirement Chen continued to practice the fighting skills that he learned and taught while in the military. As a soldier, Chen had training in a variety of weapons, including heavy infantry weapons such as the large military spear and halberd. He also learned empty hand fighting and calisthenics probably based on the popular written works of an earlier Ming general by the name of Qi Jiguang. Since much of rural China was a particularly dangerous place at the time, these skills retained practical value. Defense against bandits was vital, and once home Chen could teach family members how to defend themselves and their families.

As we age and reflect on our lives though, concerns of health and longevity become more important. Chen was no different. As someone educated and literate, Chen was familiar with meditation and breathing techniques designed to improve health, cure disease and increase longevity. Chen’s particular contribution to martial arts was to combine practical self-defense methods, including empty hand and weapons techniques, with Daoist breathing and meditation techniques. The result was a system of martial arts equally effective for both fighting and health preservation, and that could be tailored in either direction depending on the needs of the student. This martial art would eventually be known as Taijiquan 太極拳 (or T’ai Ch’i Chuan).

Chen’s Taijiquan was passed down in the Chen family village as a closely guarded secret for about 150 years. In the early 1800s the Chen family taught it’s art to an outsider for the first time, a man named Yang Luchan (楊露禪). Yang eventually left Chen village, significantly modified what he learned, and then started teaching his system to the outside world (it was Yang who is credited with calling this martial art “Taijiquan”).

Fast forward almost another 100 years and we come to perhaps one of Taiji’s greatest teachers of all times – Chen Fa Ke (陳發科; 1887–1957). In 1928 Chen left the Chen family village for Beijing and started teaching, for the first time, the original form of Taijiquan. Chen Fa Ke’s father and many men of the Chen family made their livings as armed escorts for trade caravans. This means that they would have frequently relied on their Taijiquan training in actual self-defense scenarios. Fa Ke came from this generation of practitioners – perhaps the last to use Taiji to protect themselves in life or death situations on a very regular basis. We know that on more than one occasion Fa Ke used his Taijiquan to deal with serious conflict, including fighting the bandits common to China of that day and age.

Chen Fa Ke

Hu yaozhen

FENG ZHIQIANG

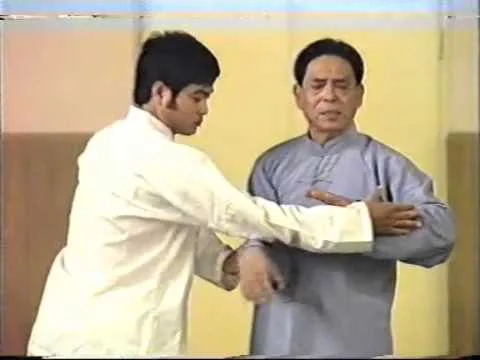

Feng Zhiqiang (馮志強; 1928-2012) was auspiciously born in the same year Chen Fa Ke started teaching Chen’s Taiji publically for the first time. Initially, as a child, Feng studied hard style martial arts such as Shaolin Gongfu and Tong Bei Quan. As a young man he had the good fortune of meeting Hu Yaozhen, one of China’s greatest master’s of Daoist Neigong (Qigong) as well as the internal martial art known as Xinyi Quan. Feng proved to be a capable student, and Hu took him on as a formal disciple and private student.

Hu and Chen Fa Ke were close friends and frequently taught together in Beijing. Hu believed that Feng was a person of unusual ability and asked Chen to teach him Taijiquan. Because of this introduction Feng also became a formal disciple and private student of Chen Fa Ke (at that time in China it was extremely unusual to have more than one lineage master). Feng quickly became one of Chen’s top disciples. In old China it was common for rival martial artists to come to a school and challenge the head teacher to a duel to test their skill. However, rather than the master him or herself meeting the challenge often their top student was sent to fight in their stead. Feng Zhiqiang was Chen’s student who was most often chosen to take on outside challenges and thus prove the worth of Chen Taijiquan as a fighting art.

Feng Zhiqiang

SEEKING THE SPIRIT OF CHEN TAIJI

As Taijiquan spread in the 20th century, the focus moved away from Taijiquan as a method of self-defense and focused more on Taiji for health purposes. This was especially true for Yang family Taiji after the simplification of forms by Yang Chengfu. For example, the word Taiji means “Grand Ultimate,” the state that is comprised of the two basic movements of the universe – Yin and Yang. As a movement concept, Taiji embraces both Yin and Yang, just as the universe embraces both Yin and Yang. What we see in many forms of modern Taiji is simply soft, slow movements. In the original form of Taiji, there is a mix of soft and hard, slow and fast, retracting inwards and exploding outwards. In other words, there is both Yin and Yang.

Over his years of training Feng Zhiqiang reintegrated a deep practice of Daoist Neigong (Qigong) with Chen’s Taiji, which in my opinion allows Chen Taiji to once again embrace its origin in combining self-defense with self-cultivation. Closer to the end of the 20th century Feng started calling his personal interpretation of Chen Taiji “Chen Style Huanyuan Taijiquan” (陳氏混元太極拳). The word “Hunyuan” means primordial chaos, or the original heart of the universe. This reminds us that the practice of Taijiquan is both as a martial art as well as a path to cultivating spirit and cultivating stillness. The first chapter of the Suwen, the foundational text of Chinese medicine says, “quiet peacefulness, absolute emptiness – the true Qi follows these states” (恬惔虛无,真氣從之). This statement is the heart of Hunyuan, and the heart of practice.

Chen Style Hunyuan Taiji Curriculum

The Chen Style Hunyuan Taiji curriculum is extensive, incorporating empty hand forms, weapons forms, Qigong/Neigong exercises, two person drills and more. However, even among Hunyuan schools the full breadth of curriculum is harder and harder to find. Here is an overview of the curriculum:

EMPTY HAND FORMS

Empty hand forms are broken down between those forms that highlight Yin (i.e., slow movements) and those that highlight more explosive, Yang movements. The latter are known as the Cannon Fist forms (Pao Chui 炮捶). Originally, as in classical Chen style Taiji, there were only two empty hand forms. These are the 83 posture long form (called Yi Lu), and the 71 posture Cannon Fist (called Er Lu). In different incarnations of Chen Taiji the exact number of posture may differ, but there are still only 2 fundamental forms - Yi Lu and Er Lu, and when Master Feng first taught Taiji these were the forms he taught. However, over time, as students had less time to study, like many other martial arts teachers Master Feng developed shorter, simplified forms to facilitate learning.

Here is the complete list of forms taught in Hunyuan Taiji (that I and my teacher both teach):

Taiji 8 Foundational Moves (Taiji Ba Fa 太極八法; various versions/patterns)

Beginners' 12 Posture Form

Basic 24 Posture Form (click here for video and movements list)

Advanced 24 Posture Form

48 Posture Form

83 Posture Form (traditional Yi Lu)

24 Posture Cannon Fist (the “Fighting Cannon” - 散手炮; Feng’s Cannon fist)

32 Posture Cannon Fist

71 Cannon Fist (traditional Er Lu)

Yin-Yang 24 Elbows Form

Hunyuan Five Directions Taiji-Qigong Form

10 Posture Seated Form

Over the course of Master Feng's life he continued to play with different versions of these forms. For example, some Hunyuan teachers teach a 37 posture Cannon Fist, or a 46 posture Cannon Fist. However, regardless of the different variations, the core theories for all the forms are the same; and the fundamental forms are still the long form Yi Lu and Er Lu.

WEAPONS

There is a wide range of weapons in Chen Taiji, including personal self-defense weapons as well as military style weapons (of classical times). Examples of military weapons include the halberd (known as the great knife 大刀, or also the Guan Dao 關刀), and the long military spear (a heavy spear of between 9 to 12 feet in length). In some contemporary Hunyuan schools only a limited number of weapons are practiced or taught, mainly because in Master Feng's later years few students spent years learning from him and thus never learned the full range of weapons forms. However, the full Hunyuan system continues to practice the complete range of Chen style weapons.

These are the weapons of Hunyuan Taiji (each weapon has a separate form):

Short Weapons:

Straight Sword (劍)

Double Sword (雙劍)

Saber (刀)

Double Saber (雙刀)

Sword Breaker (also known as the mace; 鐧)

Long Weapons:

Spear (short spear for self-defense, about 6-7 feet long; 槍)

Long Pole or Spear (based on the military spear of 9-12 feet in length; 棍)

Halberd (i.e., Guan Dao; 大刀 / 關刀)

TWO PERSON DRILLS

Two person exercises are essential to Taiji practice, and it is said, for example, that learning Taiji forms without practicing push hands is only learning 1/2 of Taijiquan. Two person drills, especially push hands, help instill the core principles that are later found in the forms.

Push Hands (including single arm, double arm, static, moving, free form, etc…)

Form applications

Qin Na (joint locking)

Two person long pole exercises

NEIGONG/QIGONG

Neigong practices are those exercises that ensure health, promote longevity, and develop internal strength. One of the key features of the Hunyuan system is the dual practice of Taijiquan as well as Neigong. Most of these exercises were not originally a part of Chen Taiji (see below for those that were). Master Feng learned them from Hu Yaozhen.

Silk Reeling exercises (from Chen Taiji)

Taiji Ball exercises (from Chen Taiji)

Daoist Neigong (without the Stick and Ruler; Internal and External Dan exercises)

Paida (Patting) Exercises

Six Sounds for Nourishing Life

24 Seasonal Node Daoyin

Various meditation practices

CHINESE HERBAL MEDICINE

Formulas for Paida practice bags

External herbal liniments (i.e., Die Da Jiu; Dit Da Jow 跌打酒) for injury management

Training formulas to assist with athletic performance, recovery, etc…

The Hunyuan system is comprehensive approach to self-cultivation, health promotion, and self-defense. For more information on group or private training in Hunyuan Taiji or in Daoist Neigong please contact us or click here for information on regular classes.